I am excited to listen to a lot of ideas and pains about infra as code and yaml. Everyone is more or less walking in the same direction. This is what I have in my mind atm. More will come. Short TTL vs Long TTL resources https://t.co/XRCOgbB3Rg

— pilesOfAbstractions (@GianArb) February 14, 2019

Recently I gave a talk at the ConfigManagementCamp about “Infrastructure as code” (slides) and I wrote an article about infrastructure as {real} code.

This post is a follow-up focused on how I identify YAML-friendly resources vs. something else.

I don’t hate YAML; I think it is a functional specification language, well supported by a lot of different languages. It works I use it when I need to write parsable and human-friendly files.

In infrastructure as code resources mean, almost everything: a subnet, an ec2, a virtual machine, a DNS record, or a pod.

I reference a single unit you can describe as a resource. The name probably comes from too much CloudFormation specification that I wrote over these years.

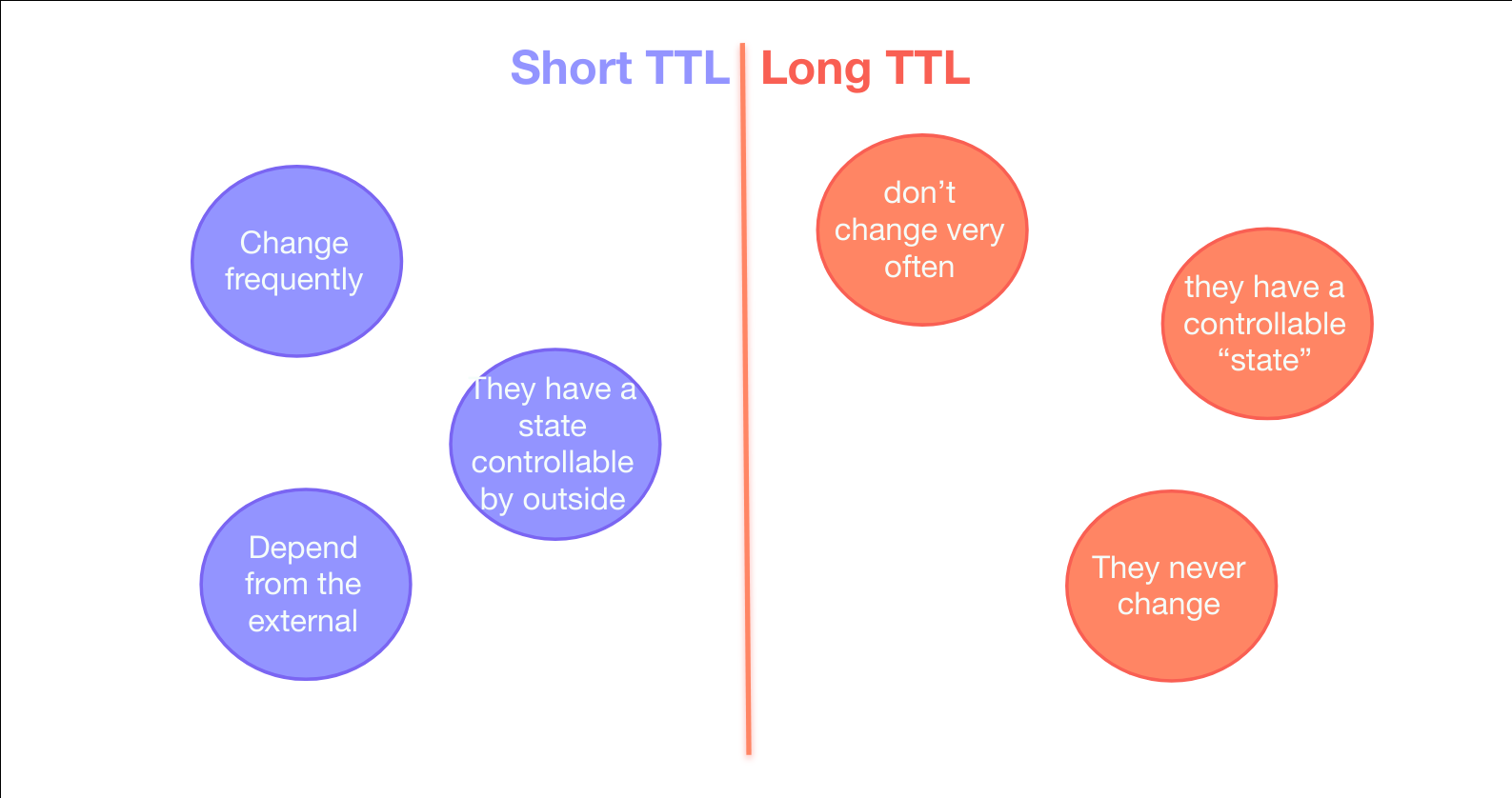

Short TTL vs. Long TTL are two different categories that I use to identify them. The resources during the evolution of your infrastructure can move between groups.

Long TTL resources are the one that doesn’t change much. For example, an AWS VPC currently doesn’t change. It gets deleted or replaced, but you can not change the cidr. A Route53 Hosted Zone doesn’t change that often. I am more confident about using specification languages and traditional tools like Terraform, CloudFormation or kubectl and YAML for these resources.

Short TTL resources changes often. Kubernetes deployment and statefulset. Route53 DNS record in my case or Autoscaling Groups. Manage the lifecycle of these kinds of resources via YAML requires a lot of automation and file manipulation that I don’t think it is safe to do. I like a lot more to interact with the API of my provider, ex. AWS or Kubernetes for them. To avoid programs that parse and modify YAML or JSON to deploy a slightly different version of a template I prefer to manipulate actual code. It is what I do every day. I have testing frameworks, libraries and a lot more patterns to use

The location of a resource is dynamic; it can jump from a category to another based on architectural decisions. One example I have is with AWS AutoScaling Groups. I like to use them to manage Kubernetes Nodes (workers). At the beginning when you need a k8s cluster to play with I usually create one autoscaling group with n replicas of the node. The node as the last command joins the cluster via kubeadm. Easy like it sounds. In this case, the autoscaling group is one. It doesn’t change that often. When your use case becomes more realistic, you need a more complicated topoligies. You need pods to go on different nodes with more RAM or more CPU or at least you need to labels or add taints to your cluster to have pods far or closer to others. This means that you end up having more AutoScaling Group with different configuration and usually, they go away and get replaced very often with varying versions of Kubernetes and so on. This dynamicity brought as side effect the request of a more friendly UX for ops, in our case integrated with the kubectl for example. That’s when we promoted AutoScaling Groups from a long TTL to a short TTL resource. We developed a K8S CRD to create autoscaling groups and so on.

The missing part is the reconciliation between long TTL and short TTL. As you can see you end up having YAML or JSON in a repository for the long TTL one and API requests for the short TTL. It means that you can not tell what’s the situation for your short TTL resources looking at your repository. You can see what you run via the kubernetes API, but that’s not what I am looking for. I think GitOps can fix the issue, but I will write more after more tests.

I tried to make these concepts as clear as possible but let me know what you think via twitter @gianarb